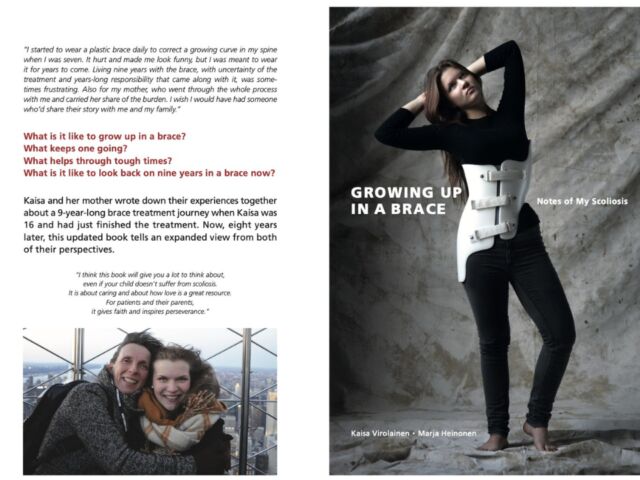

Growing Up in a Brace

Written by Kaisa Virolainen

When I was seven years old, my mother noticed something on my back. When I bent down, the right side of my back stayed higher, forming a small hump. We soon learned that bending forward is the most common way to screen for scoliosis. I would do the Adams Forward Bend Test many, many times in the next ten years.

My mom took me to a school nurse in my hometown in Finland. From there, we were directed to the local health care center, after which we got to go to the hospital to see a children’s physician. I was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathicscoliosis, a growing curvature in the spine. Because I was so young, a brace was a more suitable option than a surgery. We started an almost ten-year-long bracing journey.

The years counted ups and downs, which we wrote down together into a book after my treatment ended: Growing Up in a Bracewas published in English this spring. My mom had always been there for and with me, and for her the treatment had sometimes been even more stressful because she was worried about me. Next to sharing our journey in the book, we wanted to discuss things like motivation, mental health and parents’ experience, and share practical information about scoliosis – all things that we would have wanted to read when we were living with a brace.

The beginning of my treatment was bumpy, and my spine curvature kept on increasing despite the brace. It started straightening only when I adopted a brace mix of an overcorrecting Providence brace for the night, which actively pushed my curvature in the opposite direction, and a straight brace for the day. I wore this combination for 22 hours a day for four years, until I was 12 years old and could drop the day brace. I continued with the Providence® brace until I was 16.

The most obvious part of a bracing treatment is the physical dimension, the brace. Luckily my body got used to it quite quickly, but life with the brace wasn’t always pleasant. It made me look and feel clumsy, it made me sweat, and sometimes its pressure hurt. It was not all bad: I learned to not notice the brace for most of the time, and there were even some funny sides to the brace. For example, I got permission from my teacher to come late to school when I was learning to wear the night brace and couldn’t always sleep well. And because the day brace made holes in my clothes, I got to sit on a soft desk chair instead of a wooden school chair. Suddenly everyone in my class wanted to be with me in group projects because they got to borrow my chair.

Then there’s the less visible side, which is the mental challenge of the treatment. The primary responsibility in the brace treatment falls onto the shoulders of the child: no one could wear the brace in my place. I knew that I would have to wear the brace until my spine wasn't growing anymore, which for girls usually stopped at around 15 years old. I remember making the calculation in my head as a 7-year-old primary school student: the treatment was going to be longer than my life so far. Although I tried, it was impossible for me to comprehend the duration of the treatment.

The prospect of time is what makes any long-term disease challenging, and for me, there were moments when it was hard to see value in one day when I still had years to go. Those days were fortunately never too frequent and never too overwhelming. I learned to deal with the treatment and with the brace and everything turned out fine. At my last visit at the hospital, at 17 years old, my scoliosis curvature was below moderate 12° and was going to stay there.

I can only be happy about the outcome of my treatment. I feel gratitude towards my own younger self who found motivation to commit to the brace, and for people around me that helped me in that, and for the quality care I had access to. My mom had done her best to help me stay motivated: she had promised to buy me a horse (I loved horses) and after every visit to the hospital, we went to the cafeteria and I could eat anything I wanted (always ice cream).

Those things clearly helped, but they couldn’t erase the occasional feeling of loneliness. I always felt like I was the only child with a brace, and this didn’t make talking about my scoliosis any easier. That is something I learned only after the treatment. Knowing about others in the same situation (let alone meeting them!) would have been encouraging and surely helpful, for practical tips and motivation alike. We hope that our book can offer one form of peer support for anyone affected by scoliosis, and that way make their treatment a little bit easier.